I’m Sorry, Almira Ann

Written by Jane Kurtz

Illustrated by Susan Havice

Henry Holt & Company, 1999

96 pages

Ages 9-11

ISBN: 978-0-805-06094-2

Booklist wrote, “The many well-drawn characters make this trip along the trail a memorable one.” Short chapters, accessible word choices, and the length of this novel make it an easier reading experience than many of the Oregon Trail books that are available for young readers.

For her first young and light novel, Jane Kurtz—who was born in Portland, Oregon—reached back beyond her own persona history of growing up in Ethiopia and into her father’s family history. Jane’s great-great-grandmother traveled on the Oregon Trail. On one stop, she took off her wedding ring and hung it on a branch to make bread. The next time she remembered the ring, the wagons were far from the lunch stop, and they couldn’t possibly turn around. Jane always felt haunted by that family story and was pleased to work it into the plot of I’m Sorry, Almira Ann.

Flicker Tale Children’s Book Award Nominee 2001-02

West Virginia Children’s Book Award nominee 2001-02

Reviews

“The many well-drawn characters make this trip along the trail a memorable one. Gentle drawings help make it accessible to a somewhat younger audience than most books on the subject, but the story is as strong as many in longer novels. Good historical fiction for young readers.”

“Jane Kurtz’s newest book truly fulfills the need for accurate historical fiction for the middle grade reader. The story of Sarah and Almira Ann, two best friends, as they travel the Oregon Trail with their families moves quickly and should draw in even the most reluctant reader. Sarah rapidly moves from one adventure to another, some with unfortunate consequences. When Almira Ann is injured as a result of Sarah’s actions, it is easy to identify with Sarah as she struggles to deal with her feelings. Susan Havice’s soft pencil illustrations and colorful cover add to the warmth of the book. This is a great transition book for student s who are moving from easy chapter books to novels. Also, as an elementary school librarian, I am so pleased to be able to offer this little gem of a book to students who must choose a book “over 100 pages” for their next book report.”

Classroom Connections

Discuss the images for the book jackets created for each of the editions of book. Which one do you think is best suited for the book. Explain why. Create another jacket for the book. What do you think the jacket should show? Click on a cover to see a larger version.

Moving West Across America

- Brenner, Barbara. Wagon Wheels. Illustrated by Don Bolognese. This story chronicles the Muldie family’s trip from Kentucky to Kansas. The Muldies live in a dugout and meet Osage Indians. They also encounter wolves, panthers, and coyotes.

- Hooks, William H. Pioneer Cat. Illustrated by Charles Robinson. Nine-year-old Kate Purdy is traveling from Missouri to Oregon by wagon train. Kate helps a cuddly cat, Snuggs, stowaway on the wagon train.

- Sandin, Joan. The Long Way Westward. Carl Eric and his brother Jonas, newley arrived from Sweden in 1868, are on their way to Anoka, Minnesota.

- Whelan, Gloria. Next Spring an Oriole. Illustrated by Pamela Johnson. Follows the Mitchell family’s trek westward from Virginia to Michigan.

- Laura Ingalls Wilder authored many books about her own family’s midwestern trek from state to state, and their life when they finally settled in DeSmet, S.D. While her books do not concentrate so much on the trek as the homesteading her books do show some of the hardships of pioneer life and settling where there are few resources except those from nature. Wilder’s books are available in many forms: her original novels, picture book excepts, and excerpted chapters collected in early chapter books. Any of her titles might be appropriate in a general overall theme of pioneer life and the Westward movement.

-

In 2019, Newbery Award winning author Linda Sue Park published a middle grade novel, Prairie Lotus, about a half-Asian girl living in an American small town in 1880. The author writes, “When I read or write historical fiction, there’s one question that’s always at the forefront of my mind: Who else was there? Much of the history that we learn in school is limited to the famous names and the big events…. Prairie Lotus is my attempt to explore the incomplete story of the American frontier.”

Information about the West

- Freedman, Russell. Children of the Wild West. Photographs from a time and place where cameras were scarce. Much information about the westward movement in the United States can be gleaned from both the photos and text. Depicts the mode of dress and the pioneers’ meager possessions. Log cabins, sod houses, and schoolrooms can be compared and described. Includes pictures of Native American Indian children.

On to Oregon

- Moeri, Louise. Save Queen of Sheba. A young boy named King David uses his resourcefulness and determination to save his sister, Queen of Sheba, after they are left as the only survivors following an Indian attack on their Oregon-bound wagon train.

- Morrow, Honore. On to Oregon. Illustrated by Edward Shenton. Details the epic journey of the Sager children by covered wagon from Missouri to Oregon in 1848.

More Challenging Text for YA Readers

- Lasky, Kathryn. Beyond the Divide. A record of Meribah Simon, in journal form, afrom April 1, 1849, to June 1, 1850. Meribah accompanies her father, who has been shunned by their Amish community, West. Along the way, the two encounter cruel emigrants, the death of friends, selfishness, miserliness, rap, and finally the father’s death. But Meribah survives and makes her home in the Northwest.

- Stewart, George R. The Pioneers Go West. In 1844, the first covered wagons headed west to California. This book is based on the journal of a seventeen-year-old boy who rode in that caravan from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to Sacramento.

Activities

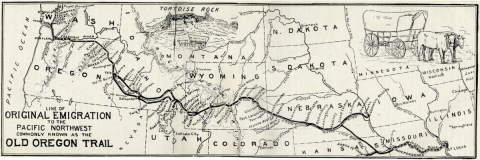

- Make a map of the route the family/person took westward. On the map mark the places and towns mentioned in the book.

- Compare and contrast the life during those times with the life you live.

- Divide a piece of paper down the middle vertically. On the left-hand side of the paper, list some “modern” convenience that you or your family uses everyday in your household—for example, a clothes dryer or washing machine. In the right-hand column opposite the item in the left column, write how the pioneer family would have accomplished the same task as the one performed by the convenience.

- From the information in the book, detail the time schedule that one of the characters might follow during a typical day. Make a time schedule for yourself.

Author Notes: The Beginnings of I’m Sorry Almira Ann

In the summer of 1959, I was visiting my grandparent’s farm in eastern Oregon for the first time that I could remember. We were back in the U.S. for the year, and I was finding it hard to make friends. I was a skinny second-grader who was used to spending days making up and acting out stories with my own sisters and the few Ethiopian girls around Maji who weren’t already working so hard around their homes that they had some time to play.

Here in the U.S., kids tended to stare at me and ask things like, “Did you see Tarzan?” So I was thrilled to arrive at my grandparents’ farm and find cousins. When Dwight, my sophisticated third grade cousin, suggested that I borrow his sister Pam’s socks so we could go wading in the swamp, it sounded good to me. Alas, our glorious, mucky adventure ended in a scolding from my stern grandmother who made me scrub the muck out of Pam’s socks and pin them dutifully on the clothesline by the apricot trees.

When I was writing my first early middle grade novel, it wasn’t so hard to slip back into that seven-year-old me to create Sarah, living on a farm in Missouri, itching to get on the road and find adventure on the Oregon Trail. “You must learn to tame your hasty spirit,” Grandmother scolds. But Sarah’s impulsiveness continues to spill over until, out on the trail, she accidentally causes grievous injury to her best friend, Almira Ann. And how do you say sorry after something like that?

If Sarah came from inside me, the details of her life in Missouri and on the trail came from years of reading about the Oregon Trail. Back in the early ’90s, I published a historical activity book, The Oregon Trail: Dangers and Dreams, that was sold for seven years along the trail in museums, gift shops, and teacher stores?

Almost everything that happens to Sarah and Almira Ann really did happen to some child traveling the trail from the girl who refused to go on without her cow to the girl who had to ride all the way to Oregon with her broken leg in a pine box. In I’m Sorry, Almira Ann, I tried to show that all women traveling the trail weren’t glum. Though most women did, indeed, find the trip heart-breakingly hard, there was also the woman who described it as “easy and interesting” and the boy who wrote in his journal that the women walked out in front, “a merry, laughing group.”

Author Notes: Family Connections to the Oregon Trail

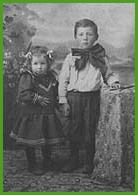

This is what my grandmother looked like as a little girl, growing up in Idaho. In this picture she is with her older brother. In 1881, her mother crossed the plains by covered wagon at the age of six. Grandma’s Aunt Ida told stories about helping gather buffalo chips for fuel and picking flowers. Grandma’s grandmother would also tell stories about what it was like, traveling on the Oregon Trail–including the sad moment when my great-great-grandmother was kneading bread and left her wedding ring hanging on a branch. By the time she discovered what she had done, the wagons were far away from that spot.

This is what my grandmother looked like as a little girl, growing up in Idaho. In this picture she is with her older brother. In 1881, her mother crossed the plains by covered wagon at the age of six. Grandma’s Aunt Ida told stories about helping gather buffalo chips for fuel and picking flowers. Grandma’s grandmother would also tell stories about what it was like, traveling on the Oregon Trail–including the sad moment when my great-great-grandmother was kneading bread and left her wedding ring hanging on a branch. By the time she discovered what she had done, the wagons were far away from that spot.

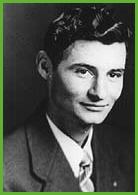

My great-great-grandmother and her husband settled in Boise Valley as the first of three generations of sagebrush homesteaders. My grandmother could remember being let out of school to watch a covered wagon go by. In 1932, when my dad was in fifth grade, my grandma and grandpa Kurtz moved across the Snake River into Oregon where they, too, became sagebrush homesteaders. The picture to the right shows my father as a young man.

My great-great-grandmother and her husband settled in Boise Valley as the first of three generations of sagebrush homesteaders. My grandmother could remember being let out of school to watch a covered wagon go by. In 1932, when my dad was in fifth grade, my grandma and grandpa Kurtz moved across the Snake River into Oregon where they, too, became sagebrush homesteaders. The picture to the right shows my father as a young man.

On my grandfather’s side, Elizabeth Fairchild, born in 1819 married Peter Kurtz, born in 1823. They had fourteen children. The first thirteen were named George, Elizabeth, Isabel, Solomon, William Alfred, Miles, John, James, Ezra, Ellis, Edward, Martha, and Lee. Maybe Elizabeth and Peter got tired of naming children because everyone in the family just called the youngest child “baby” until he got to first grade and his teacher named him Otis.

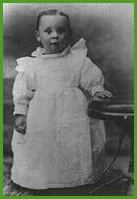

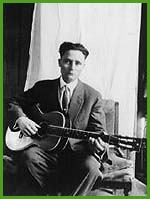

After Solomon served in the Civil War, he took the younger Kurtz children to Kansas and homesteaded there. Otis eventually caught “gold fever” and in one of the mining towns, he met and married Ida May Heaverin. Their only son was my grandfather, Marion LeRoy Kurtz, named after General Francis Marion, nicknamed the Carolina Swamp Fox, a Revolutionary War hero who harassed the British during the American revolutionary war, hiding in the swamps of South Carolina with his men. The pictures at the left shows how my grandfather looked like as a baby and as a young man. His parents homesteaded in Willow Creek, Idaho, and he didn’t go to school until he was eight years old because he had to ride a horse three miles.

After Solomon served in the Civil War, he took the younger Kurtz children to Kansas and homesteaded there. Otis eventually caught “gold fever” and in one of the mining towns, he met and married Ida May Heaverin. Their only son was my grandfather, Marion LeRoy Kurtz, named after General Francis Marion, nicknamed the Carolina Swamp Fox, a Revolutionary War hero who harassed the British during the American revolutionary war, hiding in the swamps of South Carolina with his men. The pictures at the left shows how my grandfather looked like as a baby and as a young man. His parents homesteaded in Willow Creek, Idaho, and he didn’t go to school until he was eight years old because he had to ride a horse three miles.

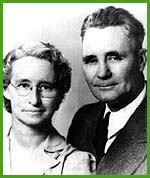

Even when Grandma was an old woman, she could clearly remember the summer she was thirteen years old, when there was a big Fourth of July picnic, and her mother made her a beautiful dress of white with little pink rosebuds. When one of the big boys named Marion Kurtz offered her a stick of gum, “that was something!” When Edith got to be fifteen, she and Marion started to do fun things together (raspberry picking, picnics) and when she graduated from high school, Marion asked her to marry him but then he went off to World War I and she went off to college. In college she played basketball and made 28 points in one game. Here’s what they looked like around that time. The coach later said, “Edith was the most natural basketball player I’ve ever seen.”

Even when Grandma was an old woman, she could clearly remember the summer she was thirteen years old, when there was a big Fourth of July picnic, and her mother made her a beautiful dress of white with little pink rosebuds. When one of the big boys named Marion Kurtz offered her a stick of gum, “that was something!” When Edith got to be fifteen, she and Marion started to do fun things together (raspberry picking, picnics) and when she graduated from high school, Marion asked her to marry him but then he went off to World War I and she went off to college. In college she played basketball and made 28 points in one game. Here’s what they looked like around that time. The coach later said, “Edith was the most natural basketball player I’ve ever seen.”

My grandma and grandpa got married in 1919 and spent 66 loving years together until my grandfather died in 1985. Grandma Kurtz lived to be 99. She lived in her own little house, and almost to the end, she had a great sense of humor and loved making doughnuts and quilts for her children and grandchildren.

My grandma and grandpa got married in 1919 and spent 66 loving years together until my grandfather died in 1985. Grandma Kurtz lived to be 99. She lived in her own little house, and almost to the end, she had a great sense of humor and loved making doughnuts and quilts for her children and grandchildren.

Primary Resources

What was daily life like on the Oregon Trail? One way we know is that many people kept journals. Even some children wrote in journals or later wrote about what their childhood trail travel was like. In an article called “Children on the Overland Trails,” in the Overland Journal, Judy Allen includes quotes and stories from some of those journals.

Here are the words of twelve-year-old Sallie Bailey, leaving home.

“My mother is heartbroken over this separation of relatives and friends. A last glimpse of our home on the hill and a wave of the hand at the old Academy and we are off.”

Most children had jobs to do. Girls often helped with milking. Mary Storey became frustrated with how hard it was to milk the family cow and wrote:

“Each of us learned to hate that old black cow. I know I have never gotten over it.”

But Margaret McLellan’s family bought a cow named Cherry, who fell over the bank while the group was climbing a steep trail. The men decided they would have to leave the cow, but Margaret said that if Cherry wasn’t going on, she wasn’t either.

“Finally the men scrambled down into the gulley, bored holes in Cherry’s horns for ropes, and pulled her back to the trail.”

Accidents often happened on the trail. Rachel Simmons, at age eleven, drove the family’s horses but was scared of one horse that would kick the board of the wagon.

Eleven-year-old Lucy Ann Henderson’s little sister Salita Jane, died after drinking some medicine from the family medicine bag.

“Parents continually warned children about jumping from the wagons,” Judy Allen writes. “Because the wagons moved slowly, dismounting appeared easy, but one slip placed a child under the heavy wheels.”

Nancy Hunt told of her sister, twelve-year-old Lizzie, who went to look for firewood and got lost.

“My mother was beside herself when they brought her in all safe and sound but very tired.”

Some things about the trip were scary. Ten-year-old Kate McDaniel wrote about a prairie storm, one of the things that frightened many children on the trail.

“We children were quaking in our bed. At each crack of thunder, which we thought would crash the top of the wagon down upon us, we would duck our heads under the pillows and draw the covers tightly over us.”

Many children had been taught to be afraid of the Native American people they saw on the trail, but one woman remembered an Indian woman who made a pair of moccasins that she wore for the rest of the trip. She wrote that when she was eleven on her trail trip:

“Indians were a constant source of wonder and delight to me.”

Lucy Ann Henderson admired a young Indian girl’s coat of soft buckskin.

“It was most elaborately embroidered with beads and of course she was quite the thing.”

Some parts of the trip were wonderful adventures. Girls and boys gathered flowers, rode horses, waded in cold streams, and were amazed at the new things they saw. Kate McDaniel remembered her favorite moment when her mother made animal cookies:

“Mother had been artist enough in cutting them out that we could pick out the different shapes. We cherished our little cookies and were loath to eat them. But finally we could not resist the temptation to take just a wee taste; so few sweets did we get those days. We would just take a bit of a nibble like mice. We would try to make them last as long as possible.”

Several journal entries made by adults focused on their experiences at Soda Springs:

“In passing their vicinity the attention of the traveler is at once arrested by the hissing noise they emit.”

—Rufus Sage

“We used this water in making our bread and found it answered all the purposes of yeast, so we carried a quantity away as a substitute for it.”

—Samuel Hancock

“The water was fine, only needed lemon syrup to render it perfect soda water.”

—J. Goldsborough Bruff

“The Sody Spring is quite a curiosity thare is a great many of them Just boiling rite up out of the ground take alitle sugar and desolve it in alitle water and then dip up acup full and drink it before it looses it gass it is furstrate I drank ahol of galon of it.”

—William J. Scott