What were your parents doing in Ethiopia?

They worked for the Presbyterian church, first in a remote area near a town called Maji and later in the capital city of Addis Ababa.

When you were growing up, did you think of yourself as an Ethiopian?

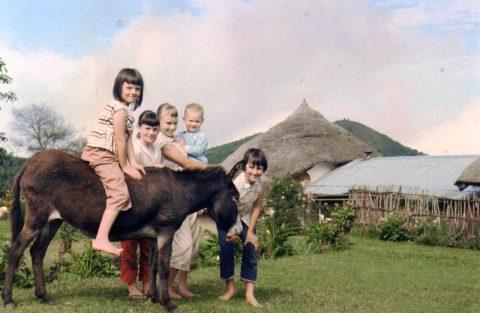

No, even though I was only two years old when my parents moved to Ethiopia, I knew I didn’t completely belong, there. For one thing, the people around me had skin from the color of honey to a dark black like a shiny obsidian rock. I had skin the color of the inside of a custard apple (if you know what that looks like) with brown dots, otherwise known as freckles. For another thing, my family and a nurse and a teacher were the only people I knew who spoke English.

Everyone else was speaking Amharic or Dizi—the mother tongue of most local people—or another language from the area. My family had some books that showed me what life was like “back home.” What I didn’t expect, though, was that we would come back to the U.S. for a visit when I was seven and I would feel even more of an outsider there.

What kind of house did you live in?

The first house I remember (in Maji) was shaped like most of the houses around–only bigger. It was round with a grass roof and a mud floor with a mat to keep the dirt down. It had a pole up the middle. Later, my grandpa came out, and he and my dad built a new house. This one still had adobe (mud and straw) walls, but it was square and had a tin roof. The rain was very loud at night on the tin roof. My mom would sometimes let us roller skate down the hall, because the floor was made of cement and there weren’t any other hard, smooth surfaces around to skate on.

What did you eat?

My whole family liked (and still likes) to eat wat and injera, which most families around us ate every day. Wat is like a spicy stew, and injera is a thin, spongy bread–like a tortilla, only with holes in it like a sponge. When my daughter first saw injera, she thought it was her napkin folded beside her plate, so that gives you some idea.

You scoop up the wat with the injera. We didn’t have a refrigerator when we moved to Maji, so my mom canned some meat. My dad also grew a big vegetable garden. In that area, not many people got to go to school, so some of the school boys, who were in their teens, worked around our house for the money to go to school. They would kill the chickens for some dinners or they’d go to the markato, once a week, to do the shopping. Sometimes people brought eggs or bananas or something, to our house. We could trade cans for eggs because the cans made a handy utensil for storing or scooping water.

Can I find your books in my library or bookstore?

Every year, tens of thousands of new children’s books are published. There isn’t enough room on the shelves of bookstores (or libraries) for every one of those books. So you can’t assume you can find any book, except maybe the award winners for the year or the ones by famous authors, in any library or bookstore. Still, a bookstore will usually order any book you ask them to order. And a library can usually order the book for you or ask for it via interlibrary loan. You can go to a book store in your community or you can order books via computer on the World Wide Web at places like Bookshop.org or Amazon.com.

Where did you go to school?

Students who went to the local school—which my parents helped keep open—learned in Amharic. Since my parents knew we would most likely eventually come back to school in the U.S., they wanted us to learn our subjects in English. So my mom taught us at home up through fourth grade. After that, each of us (six kids) went off to boarding school in Addis Ababa. Then we didn’t get home except at Christmas and summer vacation.

Weren’t you homesick?

Yes. Later, when I came back to the U.S. for college, I was homesick for Ethiopia for years. Homesickness is a feeling I know very well. That feeling is one of the sad, empty spots inside of me that nudged me to write my books.

What’s your favorite book?

That’s a little bit like asking a mom which one is her favorite child. All of my books are a little like my babies. But sometimes I ask people if they agree that the new kid in a family gets extra attention. For me, my newest book is always the favorite for a while!

Do you have any children?

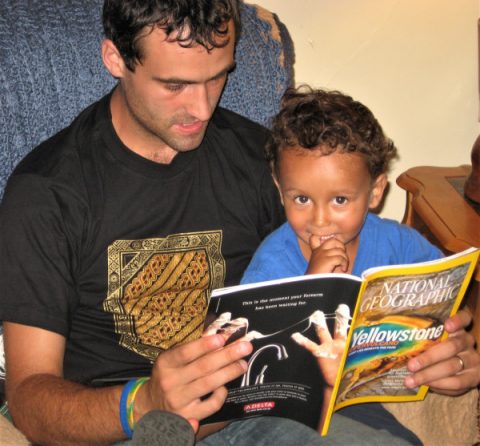

Yep! I have two sons and one daughter. All are grown now: David, Jonathan, and Rebekah. I also have two grandchildren. David is the little boy that became Christopher in I’m Calling Molly. Rebekah was the kid who loved to read almost as much as I do. Now she teaches literature to college students. I’ve gotten to see my son Jonathan reading to his children—my grandchildren. When my sons and daughter were little, I read tons and tons of books to them, which is when I first decided that I would like to write a children’s book. Until then, I had only written things for grown-ups.

Was it hard to get published?

It was very hard. I show students in schools a folder of my rejection letters from just one year–all the times editors said”no.” Sometimes, it takes a lot of failure, a lot of “no” to get to yes. A story can be pretty good and still not be good enough to get published.

How long does it take you to write one of your books?

This question, I always think, is the very hardest to answer. First of all, I work on picture books, chapter books, and novels, so obviously a longer book usually takes a longer time when I’m writing a first draft. But the truth is that picture books can be amazingly hard to get right. Quite often, I get stuck. I might have a beginning and middle but no ending. I might have an ending but not know how to get there. I might put a draft away for months or even years until I see a new path.

Even after I write a draft, that’s only the beginning. I read it over and over again to myself–or out loud–and listen to how the words sound. I think about how to pull the reader in, to make the reader feel what I’ve felt or see what I’ve saw. In Pulling the Lion’s Tail, at the tense scene where Almaz finally gets close to the lion, I struggled with how to make the reader be there with Almaz, right up next to the lion. Finally, I decided to use the sense of smell. So I asked myself, “What does the lion’s breath smell like?” I had to try a lot of different possibilities before the right one came to me.

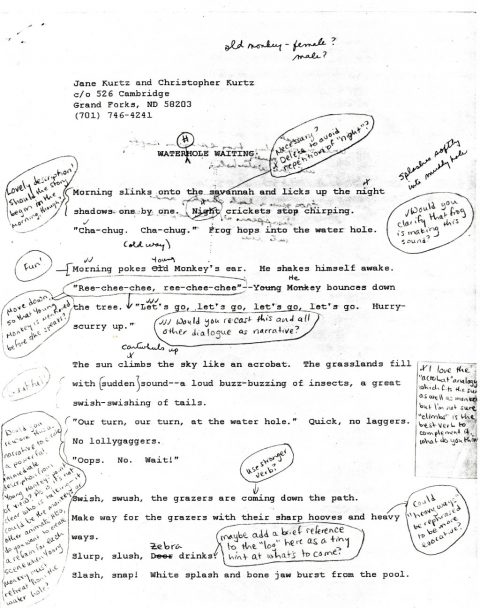

Even after I revise and revise, my work isn’t finished. My author friends and my editors read what I’ve written and give me feedback. Sometimes I feel as if I have to change every word. Here is a draft of Water Hole Waiting with editor comments, for example. It’s never easy to throw away words I worked so hard to get right—but sometimes doing that will help me find something even better.